Harold Evensky CFP® , AIF® Chairman

I couldn’t resist using one of my favorite words—lagniappe. It means a little something extra, given at no cost, somewhat like the thirteenth doughnut in a baker’s dozen. Because there are so many topics and issues I could not cover in the previous chapters, here’s my lagniappe.

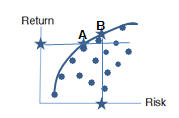

Small and Ugly May Be Beautiful. If you need more returns. One possible strategy, supported by decades of research, is to overweight a few market factors in your portfolio. Based on the original research of two well-known academics, Gene Fama and Ken French, you allocate some of your stock holdings to small companies and value stock. Over the long-term, you’re likely to be rewarded with a few extra percentage points of returns.

Maximize Quality of Life, Not Returns. It’s confusing, but after having designed many hundreds of retirement plans, it’s obvious that if you’re near or in retirement and depending on your portfolio to provide cash flow for your lifestyle, a higher allocation to bonds is likely to increase your likelihood of success at the cost of reducing the likelihood of making more money.

Hot Stocks Pay. If you’re an active trader in hot stocks, the activity will pay your broker but not you. Remember two old jokes: 1) Broker to a new client pointing out the window of his beautiful office overlooking the bay. “See that yacht; that’s my partner’s. The one next to it is Mark’s—he’s the broker next door—and the one next to that is mine.” The wise prospect asks, “Where are the clients’ yachts?” 2) How do I make a $1,000,000 in the market? Start with $2,000,000.

Safety versus Certainty. My friend Nick Murray shakes his head when he hears people talking about safe investments. He says (and he’s right): investors confuse safety with certainty. Putting your nest egg into insured CDs may offer the certainty that when they mature, you get your principal back with the promised interest; however, assuming you’re like most of us and find your expenses going up with inflation, over time your safe investment is likely to buy you less and less of the goods and services you need. This is called purchasing power erosion and it’s one of the biggest risks retirees face. The solution is to plan on a safe portfolio—one with bonds and stocks—and avoid the certainty of losing purchasing power with a safe investment.

It Doesn’t Cost You Anything Don’t You Believe It. Unless you’re the kind of person who believes in fairy tales. No professional can afford to work for free. Good investment advice is valuable, and people providing advice deserve and expect to be compensated. So it really angers me when an investor says they were told a service shouldn’t cost them anything.

Two prime examples are bonds and variable annuities. When purchasing a bond, it’s true that you’re not charged a commission. That doesn’t mean you’re not paying compensation. Bonds are sold based on something called a spread. You might be offered a $10,000 bond at 102.5. That means your cost would be $10,250. The broker may have been told by his bond department: “This bond is available at 100.5. How much do you want to add?” To which the broker responds, “Two.” And the trader says, “Fine. Done at 102.5.” The result: you’re purchasing a bond with a 2 percent markup. The markup is the fee to the broker and brokerage firm. Again, there’s nothing wrong with paying a markup, but make sure you’re told how much it is. The good news is that you can check by going to http://finramarkets.morningstar.com/MarketData/Default.jsp , a website that provides the details of most bond trades.

A Variable Annuity (VA) is another investment product that, unfortunately, a small minority of unscrupulous brokers use to take advantage of clients. The line is: “Don’t worry. It doesn’t cost you anything. The insurance company pays me.” Although factually true, it’s massively misleading because it ignores the reality of where the insurance company gets the money to pay the broker. The money comes from you, the annuity purchaser. The practice is particularly egregious because VAs typically pay relatively high commissions to brokers and they have no break points, unlike mutual funds. On mutual funds the commission drops as the purchase size gets larger. The broker gets the same percentage on a VA no matter how big the purchase.

Duration, Shmuration. Who Cares? You should. You probably know, or at least have heard (especially if you read Chapter 7, “Getting Your Money Back”), that bonds are subject to interest rate risk. That’s the risk of being stuck with a poor investment if after having purchased a bond, interest rates rise.

Consider John, new owner of a $10,000 ten-year bond purchased when it was paying 4 percent. Five years later, interest rates are up and a new five-year bond of the same quality now pays 7 percent. If John wishes to sell his bond, he would be offering his now five-year bond paying 4 percent. There is no way someone will pay him $10,000 for a bond paying 4 percent when the buyer can purchase a similar quality bond paying 7 percent. So if the owner, John, wants to sell, he’d have to sell at a discount.

That discount is interest rate risk. Most investors equate this risk with maturity—they assume a ten-year bond has significantly greater risk than a five-year bond. Sounds reasonable but it’s not necessarily true. The problem is that focusing only on maturity leaves out an important factor—the coupon, which is how much the bond issuer pays annually. The higher the coupon, the sooner the investor has some funds back to reinvest at the new, higher rate so a high-coupon bond might have less interest rate risk than a shorter-maturity, low-coupon bond. For an approximate guide to the level of interest rate risk a bond has, ask about the bond’s duration. That number will provide a very rough guide to the potential loss in value if rates rise. The measure is 1 percent for every year of duration. So a bond with a five-year duration might be expected to lose 5 percent if rates go up 1 percent or 10 percent if rates rise 2 percent. Not a perfect measure but far better than maturity.

I’ll Keep an Eye on It. When I caution clients about the risk of a heavy concentration in a single investment, they often respond, “Harold, I understand, but I keep a careful eye on it.” That sounds wise. Unfortunately, as Professor Sharpe taught us about the unrewarded diversifiable risk, that’s false confidence. It’s a risk that can blindside you.

Think about the fact that many years ago a crazy person who put poison in some Tylenol bottles threatened the business of Johnson & Johnson or consider the Gulf oil disaster that almost buried BP. Years ago, I used to use as the example of a company building a major manufacturing facility over what turned out to be a toxic waste dump. Well, one day, using that story to persuade my clients to reduce their exposure to the stock they held in the company where they had both spent their careers.

Their mouths dropped open and they said, “Good Lord! You’re right! We’ll sell out.” It turned out that just a few years earlier their company had, in fact, developed a major research facility over what later turned out to be a toxic dump and it almost bankrupted the firm.

It doesn’t matter how blue the blue chip is, the risk is there. Many years ago I warned a trustee that a portfolio allocation to AT&T stock representing about half the portfolio value was a significant risk. Unfortunately, I wasn’t very persuasive and the trustee scoffed at my warning—after all, it was AT&T. About a year later the value dropped over 50 percent. The drop had nothing to do with my having a crystal ball; it might just as well have doubled in price. The point is that the risk is real.

Counting on Gurus to Predict the Future May Be Hazardous to Your Wealth. No question about it: when doing investment planning, you need to have some opinion about future market returns. In my office, I have all of the important elements, including extensive databases, sophisticated analytical software, an expensive crystal ball, and a Ouija board. The future is mighty cloudy and surprises even the best of us.

The moral? It’s not Buy and hold, it’s Buy and Manage. Make your best estimates about the future and be prepared to change. Just don’t put too much faith in any guru’s ability to tell you where the market’s going, no matter how confident he or she may be.

This blog is a chapter from Harold Evensky’s “Hello Harold: A Veteran Financial Advisor Shares Stories to Help Make You Be a Better Investor”. Available for purchase on Amazon.